Home » Posts tagged 'imcp' (Page 8)

Tag Archives: imcp

IMC Exploration (IMCP) – Avoca, Our Mining Heritage

Excerpts from a brief history of metal mining in the Vale of Avoca, County Wicklow – by Alan Thomas and Peadar McArdle.

Excerpts from a brief history of metal mining in the Vale of Avoca, County Wicklow – by Alan Thomas and Peadar McArdle.

The Vale of Avoca is a beautiful part of County Wicklow, deservedly know as the “Garden of Ireland”. It features on the earliest known map of Ireland by the geographer Ptolemy who is said to have visited the area in 150AD. The mineral wealth of the valley has been known for centuries and prominent people have been involved in its exploration. Among the most celebrated, (although not the most successful), was the 19th century nationalist leader Charles Stuart Parnell, who was said to be obsessed by exploration progress.

An eminent geologist Sir William Smyth visiting the area in 1853 wrote of his impressions.

“There is perhaps no tract in these islands which exhibits, even to the uninitiated, an appearance so strongly stamped with the characteristics of the presence of metallic minerals. For a considerable distance on both sides of the deeply cut valley of the Avoca the face of nature appears changed and instead of the grassy or wooded slopes, or the grey rocks which beautify the rest if its course, we see a broken surface of chasms. ridges and hillocks, glowing with tints of bright red and brown, or assuming shades of yellow or livid green, which the boldest artist would scarcely dare to transfer to his canvas.”

“Here and there from among the ruins peers the white stack and house of a steam engine; or water wheels stand boldly projected against the hillside, some still neglected,  others whirling around in full activity; long iron pump rods ascend the acclivities to do their work at distinct shafts, and as long as the daylight lasts, the rattle of chains for raising the ore, and the clink of the separating hammers attest the vigour of the operations. In truth quite independently of the geological or mining interest of the place, a walk through this series of mines, especially on a sunny evening, will yield a harvest of novel and striking scenes, the effect partly of the features of the mineral ground and partly the fine distant prospects which the higher workings command.”

others whirling around in full activity; long iron pump rods ascend the acclivities to do their work at distinct shafts, and as long as the daylight lasts, the rattle of chains for raising the ore, and the clink of the separating hammers attest the vigour of the operations. In truth quite independently of the geological or mining interest of the place, a walk through this series of mines, especially on a sunny evening, will yield a harvest of novel and striking scenes, the effect partly of the features of the mineral ground and partly the fine distant prospects which the higher workings command.”

Today the beauty of the valley has reached a much wider audience, due in no small way to the success of the BBC TV series ‘Ballykissangel’ which was filmed on location in Avoca.

Today the beauty of the valley has reached a much wider audience, due in no small way to the success of the BBC TV series ‘Ballykissangel’ which was filmed on location in Avoca.

To be continued….

The Prospect of Large Gold Nuggets! – IMC Exploration

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Dr McArdle, who recently retired as Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland, has had a long term interest in the history and origin of the Goldmine River gold deposits.

Text copyright Dr Peadar McArdle 2011.

Pt 13 – The Prospect of Large Gold Nuggets!

What made Goldmine River so distinctive and important was the prospect of coming upon large gold nuggets which could provide the finder with an instant fortune. No wonder there has been such confusion over the weight, constitution and even location of the more spectacular examples. Here are some candidates for the role of largest nugget:

- “The Wicklow Nugget, found in Ballin Stream in County Wicklow, 1795.” It was owned by King George III and weighs 682g.

- Mr Atkinson, Lord Carysfoot’s agent, refused 80 guineas for a gold-encrusted quartz specimen, according to newspapers of 1795.

- “The largest specimen of native gold found in Europe as yet known, is that discovered in the County of Wicklow. It weighs 22 ounces.”

- 22oz nugget bought by Turner Camac for £80 12 shillings and presented to George III, who had it made into a snuff box.

There will always be fascination about the largest gold nugget and what happened to it. The information above is from authoritative accounts – which shows the level of confusion! So it is time to turn to Valentine Ball (1843-1895), a tall bearded man who spent 17 years with the Geological Survey of India in the search for economic minerals. He had notable success in finding coal deposits in West Bengal which are still being mined. Following a short stint in the Chair of Geology and Mineralogy at Trinity College Dublin, he became in 1883 the Director to the precursor to the Natural Museum of Ireland. He oversaw its relocation to the Leinster House premises it still occupies but was forced to resign through ill health at age 51 and died shortly after. He was clearly motivated in his new post. His interest in the gold nuggets arose from his need to label accurately any material held by the museum.

After much careful consideration, Ball concluded that the two gentlemen, Abraham Coates and Turner Camac, were the probable donors of the largest nugget to King George III and that the latter received it by early 1796. The allegation that the monarch had it made into something as trivial as a snuff box elicits the following comment from Ball, a most loyal subject of His Majesty. “That a snuff-box was made of a 22oz nugget may seem incredible, but possibly in some other form, and with an inscription, the metal may have been preserved, and this record of fact and dissipation of myth, will I trust, aid in its ultimate identification.”

With the passage of a century since its donation, it seems overly optimistic to think that it might then be found, but earnest Ball does not entirely subscribe to this view: “Although I have not been able to obtain information from Windsor Castle as to the existence of any trace of this transaction, I by no means despair of such ultimately being found.”

With the passage of a century since its donation, it seems overly optimistic to think that it might then be found, but earnest Ball does not entirely subscribe to this view: “Although I have not been able to obtain information from Windsor Castle as to the existence of any trace of this transaction, I by no means despair of such ultimately being found.”

Nevertheless the fame of the largest nugget, 22 ounces in reputed weight, did not diminish with time. In fact several models of it were made soon after its discovery and examples are now in the possession of the National Museum of Ireland, the Geological Survey of Ireland and the Natural History Museum, London....

To be continued…

Other books by Dr Peadar McArdle can be viewed on Amazon here

Where is the Gold in Wicklow’s Goldmine River district? – IMC Exploration

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Dr McArdle, who recently retired as Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland, has had a long term interest in the history and origin of the Goldmine River gold deposits.

Text copyright Dr Peadar McArdle 2011.

Pt 12 – Where is the Gold in Wicklow’s Goldmine River district?

Where is the gold in the Goldmine River district? This was well illustrated on a map published in 1971 by Tom Reeves, a professional geologist by training, but better known to Irish consumers, until his recent retirement, as the Commissioner for Energy Regulation. The main focus of placer gold was along the Goldmine River itself, downstream of Ballinagore Bridge and there are additional occurrences reported from the stream at Knockmiller further east, here called the Eastern Goldmine River. These occur both east and ESE of the Ballycoog-Moneyteige ridge. There are further showings along the Coolbawn River wich flows northwest from Croghan Kinshelagh towards Annacurragh as well as along the Aughrim River and its tributaries immediately north and ENE of the Ballycoog-Moneyteige ridge. Further away, and less directly relevant to our story, are gold placer occurrences along the Avoca and Ow Rivers. The occurrences, as well as bedrock gold, all occur in close association with the outline of the zone of volcanic rocks which extends from Avoca district. Yes, even in 1801 Fraser really did get it right: there is indeed a link between volcanic bedrock and placer gold in this area.

We have an accurate knowledge of the extent of the original gold workings in the Goldmine River area because Thomas Harding, Surveyor, and his assistant undertook an arduous survey of the river, its tributaries and surrounding mountainous terrain. Harding was an accomplished and successful surveyor, residing on Prussia Street in Dublin, but he had to share the credit for his labours with several others. The resulting Mineralogical Map, published in December 1801, gives a fascinating insight into the extent of alluvial gold and workings, as well as the old (even then!) mine workings on Ballycoog-Moneyteige ridge. But then this was no ordinary map, being executed by command of His Excellency, Philip Earl of Hardwicke, Lord Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland. It was done under the direction of Richard Kirwan, who was Inspector General of Mines, and the Directors of His Majesty’s Goldmine: Abraham Mills, Thomas King and Thomas Weaver. Kirwan had visited its location back in 1796 and now, five years later, it was being published. It was certainly a good basis for presenting the new exploration strategy being proposed by the directors. It may have been intended for official eyes only – uneducated peasants could not be expected to glean much information from such a technical document. But then they wouldn’t have desired it either, all they would have wanted was free access to the workings again!

In the aftermath of any gold rush there is an understandable concentration on finding the bedrock source of the alluvial wealth. There will be references to the ‘Mother Lode’, suggesting that the bedrock source may be even more bountiful than the daughter alluvium. However in many cases this is not the case at all. The bedrock source may have been entirely eroded during the placer formation so that no bedrock ore remains. Alternatively, the main bedrock source may be buried below surface in a position that remains inaccessible – and undiscovered. For example, the placers of the Klondyke yielded over 12 million fine ounces of gold but the bedrock there has only produced 1,000 fine ounces. This has led, and not only in the Klondyke, to a frantic search for a myriad of alternative bedrock sources: a similar situation quickly developed in the Goldmine River valley....

In the aftermath of any gold rush there is an understandable concentration on finding the bedrock source of the alluvial wealth. There will be references to the ‘Mother Lode’, suggesting that the bedrock source may be even more bountiful than the daughter alluvium. However in many cases this is not the case at all. The bedrock source may have been entirely eroded during the placer formation so that no bedrock ore remains. Alternatively, the main bedrock source may be buried below surface in a position that remains inaccessible – and undiscovered. For example, the placers of the Klondyke yielded over 12 million fine ounces of gold but the bedrock there has only produced 1,000 fine ounces. This has led, and not only in the Klondyke, to a frantic search for a myriad of alternative bedrock sources: a similar situation quickly developed in the Goldmine River valley....

To be continued…

Other books by Dr Peadar McArdle can be viewed on Amazon here

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold pt 11 – IMC Exploration

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Dr McArdle, who recently retired as Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland, has had a long term interest in the history and origin of the Goldmine River gold deposits.

Text copyright Dr Peadar McArdle 2011.

Pt 11 – Pocket history of Avoca’s volcanic history

We cannot identify the specific volcano responsible for the region’s volcanic rocks: it is either buried deep underground and out of sight or it was destroyed by subsequent geological events. But we do know it dominantly spewed out ashes, because plentiful evidence of them remains in the rocks around Avoca. Low viscosity magma like basalt will usually give rise to lavas that flow downhill with the speed and consistency of thick broth. Rhyolitic and similar high-viscosity magma, on the other hand, is generally very gas-rich and erupts explosively. Avoca’s magma was predominantly of rhyolitic composition and so gave rise to ashes. Ash clouds would have billowed skywards from the volcanic crater and spread out over the surrounding seas, dropping their ash loads onto the sea floor. The ashes became incorporated into seabed-hugging and sediment-charged water currents called turbidity currents, which surged rapidly downslope and lost their sediment load when they reached flat-lying seafloor in water depths of about 200 metres. Thus developed the sediments that now form the bulk of the Avoca rock sequence.

So where would Avoca’s volcano fall on the scale of recent volcanic eruptions? Probably somewhere in the middle, outshone by examples such as Mount St Helen’s and Krakatoa. Think of the 1990’s Montserrat eruptions in the Caribbean in order to imagine the overall scale and setting.

But where are the metals for which Avoca (and indeed Croghan Kinshelagh) is famous? We know that mining took place in the vicinity of the Vale of Avoca since at least 1720. The suggestions of earlier outputs of metals extend back to Ptolemy’s time but alas are based on speculation, however tantalising. The recorded Avoca production amounts to 16 million tonnes of copper ore containing 0.6 percent copper and 5 percent sulphur. Even more prolonged, but on a smaller scale, was the output of iron ore from the Ballycoog-Moneyteige ridge on the northwest flank of the Goldmine River Valley. These workings are believed to have been operated by the Vikings and I have a suspicion their output may have been used in the Dublin of their era.

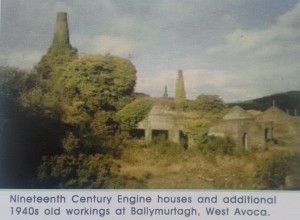

The Avoca mine frequently had but marginal profitability, especially since it re-opened in 1958, and it required Government support in its final years. Most ore was extracted from the intensive workings of West Avoca, which reached a depth of 300m below surface, but the environmental impact was greater in East Avoca where shallower workings were more extensive. The main open pits, which contributed over 30 percent, were in East Avoca. At least one of the open pits, Cronebane, gave rise to extensive waste which formed a significant dump that was subsequently used to partially backfill the pit itself. The Ballymurtagh Open Pit in West Avoca became a landfill facility for County Wicklow in the 1980’s before finally closing some years ago...

The Avoca mine frequently had but marginal profitability, especially since it re-opened in 1958, and it required Government support in its final years. Most ore was extracted from the intensive workings of West Avoca, which reached a depth of 300m below surface, but the environmental impact was greater in East Avoca where shallower workings were more extensive. The main open pits, which contributed over 30 percent, were in East Avoca. At least one of the open pits, Cronebane, gave rise to extensive waste which formed a significant dump that was subsequently used to partially backfill the pit itself. The Ballymurtagh Open Pit in West Avoca became a landfill facility for County Wicklow in the 1980’s before finally closing some years ago...

To be continued…

Other books by Dr Peadar McArdle can be viewed on Amazon here

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold pt 10 – IMC Exploration

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Dr McArdle, who recently retired as Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland, has had a long term interest in the history and origin of the Goldmine River gold deposits.

Text copyright Dr Peadar McArdle 2011.

Pt 10 – Volcanic Rock Formations

The volcanic rock parallel extending from the Croghan Kinshelagh area to Avoca and Rathdrum has been studied by geologists since Fraser’s map first appeared so that we have a good understanding of their age and how they formed. Mind you, not all rocks are uniformly well exposed so our knowledge of them is a bit uneven. Nevertheless over the last thirty years we have learned how they fit into the global kaleidoscope of changing continental and oceanic shapes and positions, a sequence of patterns which has been predicated by plate tectonics and seismic events. Sadly the consequences are determined as much by the effectiveness of the local construction codes as they are by the intensity of the seismic event itself. The Earth is a truly vibrant organism and we are not always in harmony with it.

One implication of this context is that Wicklow’s landscapes have been far from constant throughout its geological history. The widespread siltstones and sandstones all accumulated at a time when deep sea covered the Wicklow area. Land would not have been visible in any direction over most of the period that sediments formed and yet the influence of the land would have been discerned. For this region was part of an ocean, Iapetus Ocean, which formed here (and was in time destroyed) long before there was any hint of the emergence of the modern-day Atlantic Ocean. The sediments were deposited on the southeast continental margin of this long-vanished Iapetus Ocean and were subsequently churned up and re-deposited in deeper water. This was achieved through the operation of sediment-laden deep-sea currents triggered by earthquakes or major storms. While considerable thicknesses of sediment were thus laid down in a matter of days, there could have been time lapses of centuries between each pulse. The different nature of the rocks formed reflects the different sources tapped for sediment over time.

But inexorably, although imperceptible to an individual observer, the ocean itself was now contracting in size and the continents on opposing margins were approaching each other. They would eventually collide with each other, but before that happened, a series of volcanoes would develop in between, like beads strung out on a gigantic necklace which marked their junction. These volcanoes gave rise to the diversity of associated volcanic rocks, including those in Fraser’s golden zone of southwest Wicklow. The opposing continental margins did crash into each other, with one causing the other to sink deep into the Earth’s interior. All of the pre-existing rocks were stressed and heated, with the finer grained sediments developing a slaty cleavage. As increased heat partially melted the descending rock sequence, the resulting liquid magma buoyantly ascended along fault lines and fractures in the Earth’s crust, forming the considerable bodies of granite for which Wicklow is celebrated. This was the final act in the destruction of the Iapetus Ocean: the forces of plate tectonics would soon be realigned in a new European configuration that would lead to the next phase in Earth’s enthralling history.

But let us revert to the necklace of volcanoes which will feature prominently in our story. We are now entering the Ordovician Period, a fascinating phase in Earth’s evolution, which lasted from 488 to 444 million years ago, a relatively extensive period of 56 million years. At the global level, the Earth was a very different place than it is today. Continents were all clustered in the Southern Hemisphere, and this is where the northern and southern halves of Ireland would eventually come together as the Iapetus Ocean finally closed. There was a very complex array of volcanoes, which were fed an abundant supply of lavas due to some spectacularly intensive convection, or ‘hot spot’, operating in this part of the Earth’s mantle. It was right in the middle of this fascinating Ordovician Period, about 450 million years ago, that the volcanic rocks of the Croghan Kinshelagh and Avoca district were formed..

But let us revert to the necklace of volcanoes which will feature prominently in our story. We are now entering the Ordovician Period, a fascinating phase in Earth’s evolution, which lasted from 488 to 444 million years ago, a relatively extensive period of 56 million years. At the global level, the Earth was a very different place than it is today. Continents were all clustered in the Southern Hemisphere, and this is where the northern and southern halves of Ireland would eventually come together as the Iapetus Ocean finally closed. There was a very complex array of volcanoes, which were fed an abundant supply of lavas due to some spectacularly intensive convection, or ‘hot spot’, operating in this part of the Earth’s mantle. It was right in the middle of this fascinating Ordovician Period, about 450 million years ago, that the volcanic rocks of the Croghan Kinshelagh and Avoca district were formed..

To be continued…

Other books by Dr Peadar McArdle can be viewed on Amazon here

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold pt 9 – IMC Exploration

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Dr McArdle, who recently retired as Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland, has had a long term interest in the history and origin of the Goldmine River gold deposits.

Text copyright Dr Peadar McArdle 2011.

Pt 9 – Born of Fire & Frost

Within a few short years of its discovery, the public reputation of the Goldmine River had been brought into line with a harsh reality. Yes there certainly was alluvial gold there, and it could be spectacular, but its quantity was limited and no local bedrock source – no Mother Lode – had materialised. Its workings were abandoned, apart from the periodic patrols of the militia stationed there. Perhaps only the surreptitious attention of nocturnal neighbours would preserve its memory for future generations. Would this be the end of the matter or could there yet be other twists to the story? A pessimistic outcome seemed inevitable and would perhaps be in keeping with the depressing disappointment of recent political and military events throughout Ireland.

Yet there had to be a good geological reason to explain the exuberant workings in the first place. At this very time, Robert Fraser was finalising the first geological map of the County of Wicklow, illustrating the distribution of its varied rock types with a variety of colours. Fraser had already prepared reports on agriculture and related aspects of Devon and Cornwall and now he would report to the (Royal) Dublin Society on the current state of County Wicklow. And there in the southwest corner of the county, including the district around the Goldmine River and Avoca, was a distinctive group of rocks for which Fraser had reserved a uniquely golden colour. What could this mean? He was certainly aware of the area’s copper and gold resources, stating that it was “abounding in metallic (sic) productions to an extent not by any means ascertained, but which will in all probability be capable of employing the most extensive capital and an indefinite number of hands.”

To understand the distribution and origin of gold in the sediment of the Goldmine River valley we must first consider its geological context. Many visitors to Dublin will take the time to explore the scenic landscape of the neighbouring Wicklow region, a landscape that many residents may take for granted and which is sculpted from its diversity of rock types. The most extensive rock group, called the Ribband Group from its striped appearance in outcrop, comprises mudstones and siltstones which have been converted to slaty rocks. They form the lower ground, mainly farmland, of eastern Wicklow as well as many of the lower hills, along many of whose forest roads it is exposed. The mountainous spine of Wicklow is formed of a very different rock – Leinster Granite, which extends to the southern suburbs of Dublin City. In the past it was extensively quarried for building stone. Among its most celebrated exposures, between Blackrock and Whiterock Beach are those at Joyce’s Sandycove Martello Tower.

The green muddy sandstones of the Bray Group are well known to travellers on the M11 / N11 route where they are splendidly exposed between Newtownmountkennedy and Rathnew. Thick creamy-coloured quartzite beds also make their appearance here, but they are best exposed in the surrounding hills where they form ridges with serrated skylines, not to mention the isolated cone of the Sugarloaf Mountain which causes it to be misidentified as a volcano on occasion. Additional impure green sandstones form the Kilcullen Group in west Wicklow and extend into adjoining County Kildare. These can be inspected at the roadside in Glending, west of Blessington town, and also further south, along the N81 near Dunlavin. The final group of rocks, the Duncannon Group is among the most restricted in extent, and forms a relatively narrow zone that extends from the Waterford-Wexford coastline northeastwards to terminate around Arklow Head. It consists of volcanic rocks, the products of lavas and ashes ejected from ancient volcanos whose outlines have long since vanished. There is a second parallel, but subsidiary, zone of these rocks which is very important for our story. It extends from Croghan Kinshelagh area to Avoca, and further northeast to Rathdrum and beyond. Yes, this is Fraser’s golden zone.

The green muddy sandstones of the Bray Group are well known to travellers on the M11 / N11 route where they are splendidly exposed between Newtownmountkennedy and Rathnew. Thick creamy-coloured quartzite beds also make their appearance here, but they are best exposed in the surrounding hills where they form ridges with serrated skylines, not to mention the isolated cone of the Sugarloaf Mountain which causes it to be misidentified as a volcano on occasion. Additional impure green sandstones form the Kilcullen Group in west Wicklow and extend into adjoining County Kildare. These can be inspected at the roadside in Glending, west of Blessington town, and also further south, along the N81 near Dunlavin. The final group of rocks, the Duncannon Group is among the most restricted in extent, and forms a relatively narrow zone that extends from the Waterford-Wexford coastline northeastwards to terminate around Arklow Head. It consists of volcanic rocks, the products of lavas and ashes ejected from ancient volcanos whose outlines have long since vanished. There is a second parallel, but subsidiary, zone of these rocks which is very important for our story. It extends from Croghan Kinshelagh area to Avoca, and further northeast to Rathdrum and beyond. Yes, this is Fraser’s golden zone.

To be continued…

Other books by Dr Peadar McArdle can be viewed on Amazon here

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold pt 8 – IMC Exploration

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Dr McArdle, who recently retired as Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland, has had a long term interest in the history and origin of the Goldmine River gold deposits.

Text copyright Dr Peadar McArdle 2011.

Pt 8 – A total of just over 944 ounces of gold recovered

Notwithstanding Weaver’s failure to secure funding for the tunnel, he did open 12.8km of trenches down to bedrock, quite an extensive undertaking. The depth of overburden gradually thins upwards towards along the valley slope and at the point where it almost disappears in Ballinvalley (upslope from the Red Hole) and adit was driven into the mountain, but only for 320m. Additional adits and shafts were also opened in the district. The evidence of all these workings still remain in the valley and the occasional radial trench forms the basis of its modern drainage. However it was all to no avail. None of the quartz veins had any gold particles, despite thorough sampling and rigorous chemical analysis, and this suggested there was no local source for the alluvial gold.

Weaver’s efforts were terminated in 1803, with another 12kg of gold recovered since 1800, but the military barracks remained occupied with a party of troops for some years afterwards just in case the neighbours were distracted once more. In 1819 Weaver summarised the outcome of Government operations from 1796 to 1803. A total of just over 944 ounces of gold was recovered. Just 6.3 percent (almost 59 ounces) was sold as specimens at £4 per ounce, melted and cast into ingots by Weaver. The vast bulk, 93.7 percent, or 885 ounces, was sold to the Bank of Ireland, but at a slight premium. Weaver notes that there was a loss of 4.25 percent gold in the process. The total aggregate value of native and ingot gold was over £3,675.

Eminent scientist Richard Kirwan claimed that little or no gold is replenished by modern stream action. He considered that, even where replenishment was taking place, based on eighteenth century European experience, it would be limited to minor quantities of tiny flakes. Accordingly he considered it could “be advantageous to none but the poorest people.” It is unusual for persons to be disdainful of small amounts when they relate to commodities such as gold and in this attitude I suspect that Kirwan was quite different from the neighbours.

So a dichotomy of views arose and surprisingly would persist to modern times. On the one hand, officialdom saw no potential for a viable operation in Wicklow and, anyway, would not countenance investing taxpayers’ money in a speculative venture involving gold. Feelings towards Goldmine River in Dublin or London would always be ambivalent. On the other hand, local residents and prospectors did not share these opinions. They were not appalled by unruly assemblies and workings, nor were they discouraged by the risk of poor returns. So the interweaving of these opposing views would form the historical tapestry for these gold workings.

So a dichotomy of views arose and surprisingly would persist to modern times. On the one hand, officialdom saw no potential for a viable operation in Wicklow and, anyway, would not countenance investing taxpayers’ money in a speculative venture involving gold. Feelings towards Goldmine River in Dublin or London would always be ambivalent. On the other hand, local residents and prospectors did not share these opinions. They were not appalled by unruly assemblies and workings, nor were they discouraged by the risk of poor returns. So the interweaving of these opposing views would form the historical tapestry for these gold workings.

To be continued…

Other books by Dr Peadar McArdle can be viewed on Amazon here

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold pt 7 – IMC Exploration

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Gold Frenzy, the story of Wicklow’s gold – An excerpt from the book by Dr Peadar McArdle.

Dr McArdle, who recently retired as Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland, has had a long term interest in the history and origin of the Goldmine River gold deposits.

Text copyright Dr Peadar McArdle 2011.

Pt 7 – The likely source of gold lies in the mountain’s quartz vein.

When work resumed in September 1800, First Lt Weaver came into his own. The Commissioners now recommended to the Government that work be extended beyond the simple collection of alluvial gold to include a search for any gold bearing veins in the bedrock. The Government, like any government might do, had finally abandoned any pretence that it was focussed only on preventing the assembly of mobs. Let’s go for gold! Weaver worked on the assumption that the alluvial gold would be sourced in quartz veins on the higher ground surrounding Croghan Kinshelagh Mountain.

In their report, the Commissioners described the progress of the workings and the weight and value of gold recovered in considerable detail. They also investigated reports of gold occurrences in all neighbouring streams and recorded their relative success. Because gold sometimes adhered to quartz, they concluded that quartz veins were the source of the gold – and very likely some of the many such veins occurring on Croghan Kinshelagh mountain itself. The workings were not without their own tribulations, for the authors reported that their utensils (at Monaglogh): “were destroyed by some persons unknown, for the discovery of whom a reward of 20 guineas was offered without producing the desired effect and the trial was not resumed.” While minor compared to the events of May 1798, clearly the neighbours had not entirely acquiesced in their imposed state of inactivity.

Convinced that a viable bedrock gold source lay in quartz veins on the higher slopes of Croghan Kinshelagh, the Commissioners proposed to continue working the river bed, opening trenches and even tunnelling until this idea had been fully tested. Indeed they had one daring if risky idea: to open a tunnel, at right angles to the principal direction of the veins, straight through the mountain at the highest level where gold had been discovered in the river bed. While the other proposed workings could be relied upon to produce a profit, this new concept was much more risky.

In considering the programme of work recommended by Abraham Mills and co-workers, the Government had the weighty views of eminent scientist and President of the Royal Irish Academy, Richard Kirwan. In his report, published as an appendix to that of Mills and co-workers, he was complimentary about the operations themselves: “As to the method of extracting gold from the sand, none, I believe, can be more ingeniously contrived nor more successfully applied, than that employed by Mr Mills. The real interest, however, would have been his views on the source of the gold, the future of the operation and especially in the proposed tunnel. He did not disappoint.

He agreed the likely source of gold lay in the mountain’s quartz veins but concluded that the gold was derived not by modern river action but “by ancient inundations; I say ancient, because modern inundations convey none, as Mr Mills (at my request) having tried has experienced.” Modern rivers, in his view, did not have the power to move downstream nuggets of the sizes known from Goldmine River. He was not averse to prospecting on a limited scale being undertaken in the upper reaches of the various streams and ravines. But as to the idea of driving a tunnel straight through the mountain to the other side, well he was very cautious.

This must have been sweet music to the economical ears of those in HM Treasury! Nowadays a cost-efficient set of boreholes would be attempted, but that option was not available to Weaver and tunnelling techniques were primitive, slow and expensive. Kirwan appended a later note (dated 1 October 1801), after the mountain had been surveyed, indicating the proposed tunnel would be 8,862ft (2.72km) in length. He concluded, “The expense I cannot estimate” – another damning uncertainty in the eyes of HM Treasury. The tunnel was never driven.

This must have been sweet music to the economical ears of those in HM Treasury! Nowadays a cost-efficient set of boreholes would be attempted, but that option was not available to Weaver and tunnelling techniques were primitive, slow and expensive. Kirwan appended a later note (dated 1 October 1801), after the mountain had been surveyed, indicating the proposed tunnel would be 8,862ft (2.72km) in length. He concluded, “The expense I cannot estimate” – another damning uncertainty in the eyes of HM Treasury. The tunnel was never driven.

To be continued…

Other books by Dr Peadar McArdle can be viewed on Amazon here

CEO Interview: Partnership with Koza Gold a great opportunity for IMC Exploration (IMCP) in Ireland

The Finance Director of IMC Exploration PLC, Nial Ring, joined Alan Green, CEO of Brand Communications, on the Tip TV Finance Show to discuss the projects and developments ahead for the company.

What does the future hold for IMC Exploration?

Ring began by outlining that IMC has 5 precious metal and 10 base metal licences in Ireland, and has entered a joint venture with Koza Gold. He continued that Koza Gold has invested 1.4 million euros for 55% of the precious metal licences, and Ring already noted that they have drilled over 1000 metres, have analysed 420 drill holes and spent plenty of time and money investigating in Ireland. He highlighted that IMC Exploration is preparing to be fully-listed on the stock market in order to be able to raise capital for future deals with Koza Gold or other firms interested in working with IMC.

Alan Green discusses CEB Resources, Nanoco & IMC Exploration on the ADVFN podcast

Alan Green discusses CEB Resources (CEB), Nanoco (NANO) & IMC Exploration (IMCP) with Justin Waite on the ADVFN podcast.

Alan Green discusses CEB Resources (CEB), Nanoco (NANO) & IMC Exploration (IMCP) with Justin Waite on the ADVFN podcast.

The interview on podcast 341 is 21 minutes,20 seconds in. Click here to listen.